The murder of Sarah Payne: Two decades on

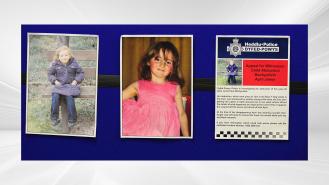

On 1st July 2000, eight-year-old Sarah Payne disappeared. It became a high profile landmark case and two decades later much has changed in the aftermath of Sarah’s death.

Sarah Payne had been playing near her grandparents’ home in Sussex with her brothers and sisters when she disappeared. She had run away from the others to go back to her grandparents’. When she reached the road, she was abducted, snatched by a man in a white van.

Within hours, police had launched a country-wide campaign to find her, but 17 days later, her naked body was found. Local paedophile Roy Whiting was arrested and charged with the murder. On 12th December 2001, he was found guilty and sentenced to life.

When it came to police making a list of possible suspects in Sarah’s disappearance, Roy Whiting led it. In fact, he was arrested for the first time (out of three arrests during the case), the very day after she disappeared. He had already been jailed and put on the Sexual Offenders Register in 1995 (one of the first in the UK to be added to it) after he abducted and sexually assaulted a nine-year-old girl. He had been sentenced to four years, but released after two.

But news of Whiting’s previous crimes only came to light after his trial had ended. When they did, they sparked outrage: could Sarah’s murder have been prevented if her parents, Michael and Sara Payne, had known about Whiting? Other parents worried paedophiles could be living in their neighbourhoods, without their knowledge. Were children safe?

It prompted one of the biggest changes that has happened since Sarah’s death: Sarah’s Law. Michael and Sara Payne began a campaign, in conjunction with the News of the World, for a change in the law that would give parents the right to know about local sex offenders living in the area. In 2011, 11 years after they began, Sarah's Law was rolled out across England and Wales.

The law allows people to seek information from the police on whether someone connected to their child has a record of committing crimes against children. In the first year alone, it was announced that the law had protected more than 200 children. In 2013, the BBC reported that 700 paedophiles had been identified: one in seven of the 5,000 requests for information made revealing a sex offender.

But that isn’t the only change that has occurred since 2000.

The case received a huge amount of media attention with the police releasing e-fits, organising events to garner more press and responses from the public and even pop group Steps making an appeal. But a lot of the attention came thanks to the efforts of the Payne family, who worked tirelessly to ensure their daughter stayed in the public eye. They appeared in television appeals and news conferences days after Sarah’s disappearance; they did photo opportunities; published their private home videos; the other Payne children spoke out, as did their grandfather; Sara Payne briefed local journalists herself. And it worked.

At the time, this was more than was expected from the families of missing children. But in the ensuing 20 years, it’s become more commonplace. Just look at the way Kate and Gerry McCann have kept Madeleine’s case in the news, years after her disappearance.

The media attention wasn’t always a force for good, though. In the aftermath of Sarah’s disappearance, the News of the World began publicly ‘naming and shaming' sex offenders by printing their photos. Plans to identify thousands more were only scrapped after innocent people were attacked: vigilantes gathered in mobs, rounding up wrongly identified men, as well as known paedophiles. Innocent families were forced out of their homes after being accused of harbouring criminals. One woman was even targeted because her neighbours confused ‘paediatrician’ with ‘paedophile’. The police claimed it could be putting investigations and children at risk.

Then in 2002, the Sun was accused of getting computer expert Christopher Branscombe, who worked for the law firm working on Whiting’s trial, to take documents relating to him, paying him £2,500. He later also sold the documents onto the Mirror for £2,000, the Daily Express for £1,000 and contacted the Daily Mail, but was arrested before he could meet with them.

And that’s not all. After news of the News of the World’s phone-hacking scandal broke, it was revealed that Sara Payne was also a target of the paper’s private investigator, Glenn Mulcaire, along with other victims’ families.

In 2020, the landscape looks different. For starters, NotW no longer exists and the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO), regulating the newspaper and magazine industry, was set up in 2014.

But is there is less media scrutiny surrounding such cases? No. In 2014, the McCanns sued the Sunday Times for libel, after it printed a story that falsely claimed they withheld evidence from the police. And the family has spoken about a press that has vilified them, accusing them of being complicit in their child’s disappearance.

And other families have also suffered. Though it has become commonplace for victims’ families to work with the media in the way the Paynes did years before to engender the help of the public and dig up information and leads, it’s also led to questions of what cases are covered and how the press reacts to different families. Case in point, Shannon Matthews, whose mother, Karen, in the wake of her daughter’s disappearance, was lambasted, ostensibly for not being the ‘right kind’ of victim. She also received less press coverage

20 years on, Sarah Payne’s case has left a lasting legacy. The law has been changed to try and prevent similar crimes, earning her mother, Sara, an MBE in the process and no doubt, saving other children. And much has changed in how victims’ families are treated by the press (for better and for worse), too. But is there still more work to be done for similar families? Yes.