Do child abductions happen more in summer?

Summer is supposed to be the happiest and most idyllic of seasons, yet there also seems to be an ominous correlation with grotesque acts of child murder. From Sarah Payne to the Soham murders, kids seem to have been targeted in the period stretching from the end of spring to the end of summer. What might be the reasons for this and is it a phenomenon based on empirical facts or mere media perception?

Let’s consider the various crimes, which each exemplify a key reason why summer and child abductions/murders may have a cause-and-effect connection.

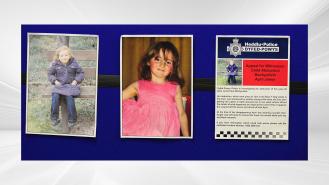

In early August 2002, a crime was committed which would appal the nation and make two ordinary girls into tragic icons, their smiling faces reproduced endlessly in the media. The girls were Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman of Soham, Cambridgeshire – best friends who vanished into thin air while out and about in their seemingly safe home town. They wore matching Manchester United shirts, posing for a photograph together just hours before their murder. It was this image that was emblazoned in the media endlessly in the ensuing days and months. As Holly’s mum later said, “It is our last picture of our daughter, yet it represents something evil – that is exquisitely painful.”

Summer brings with it a kind of liberation for children. Not just from school, thanks to the almost unimaginably long and lovely summer break, but from everyday parental rules as well. The days are long, people socialise for longer, evenings no longer feel like evenings.

Holly and Jessica were at a Sunday afternoon barbecue on the day they died, and it must have felt like the quintessential summer’s day – grown-ups coming and going, enjoying the easy-going outdoor ambience, less vigilant or aware than normal. When the girls went for a wander around Soham, it was a long while before the adults even realised they’d left the house. In fact, it was only hours later, when guests at the barbecue idly commented that the girls were being very quiet indoors, that the alarm was raised.

"It is our last picture of our daughter, yet it represents something evil – that is exquisitely painful."

It’s hard to imagine kids being able to casually come and go like that in any season other than summer, when front and back doors can so easily be left open, and when many parents may not want to spoil the seasonal bliss by being too restrictive.

Of course, whether family members are close by or not, playing outside will always present increased risks to children compared with, say, staying safely indoors playing videogames and watching the TV. In this sense, the fine weather of summer is itself a risk factor. Sarah Payne was just eight when she went missing in July 2000, while playing out in the West Sussex countryside on a fine day.

It wasn’t that nobody knew where she was. Her siblings were close by, and they had all been playing in a cornfield close to their grandparents’ home. It was during the casual confusion of playing together that Sarah ran through the field, hotly pursued by one of her brothers “I was three quarters of the way across the field when I turned round to see where the others were,” he later said. In that split second, he lost sight of Sarah forever. But he did glimpse a van being driven by a scruffy, smiling, waving man with yellow teeth.

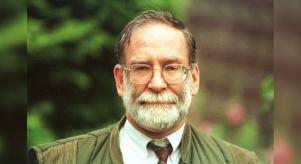

In the words of crime writer Nicci Gerrard, there was something terrible and elemental about the circumstances: “a little girl, running home across fields, is snatched by a stranger in a van, like a nasty modern fairy tale (many of us probably don't even recall Roy Whiting's name - rather than being an individual for us, he became the wicked wolf, the fictive bogeyman).”

Whiting, the lurking monster in the field, took an opportunity provided by the tranquil temperature and the sense of fun which summer bestows upon ordinary kids in the rolling British countryside. It is the easy-going atmosphere of good weather which can allow terrible people to take advantage – think of the vanishing of Madeleine McCann on holiday, made possible by the warm serenity of the surroundings drawing adults away from the apartment complex.

But the truth is more complex than these examples make it seem. It could well be that crimes committed during the summer garner more media attention because the news cycle is slower elsewhere. Politics is put on hold, after all, and more space is traditionally given over to human interest stories.

This could be one reason why we all remember Sarah Payne and Soham, but few recall the murder of Daniel Handley, a 9-year-old abducted and killed by a pair of paedophiles in October 1994, well after the hot days of summer. Or Paige Doherty, the teenage who vanished in March 2016, and was later found to have been brutally killed by a local deli owner.

It might therefore FEEL that more kids are abducted or killed in summer, when it’s actually more a matter of our perception. There are also those cases which contradict the summer theory, such as the murder of April Jones, whose horrific murder in Wales in autumn 2012 generated as much media attention as Soham had done in summer. How much does the calendar context matter – both in terms of the season itself, and the workings of the media? It may, ultimately, be impossible to say for certain.