Helen's Law

When a person goes missing, a clock starts ticking. With every passing second, the chances of a happy resolution – a joyful reunion with someone still living and breathing – diminish. But what happens if it’s the worst-case scenario? New true crime series When Missing Turns to Murder looks at killings where the victims’ bodies have never been recovered: the anguish it causes those closest to the lost, the difficulties it presents to detectives and courts, and the maddening motivations of the killers who stay stubbornly silent.

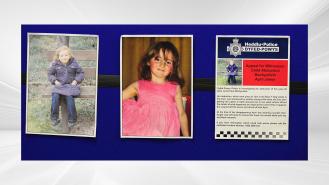

One of the most significant cases covered in the series is the murder of Helen McCourt, a young woman who went missing early one February evening in 1988. Excited about a date with her new boyfriend later that night, Helen was on her way home from work in Merseyside – a mundane journey during which she went missing after alighting from the bus. Minutes later, a scream was heard from the vicinity of a pub. The landlord of that pub was Ian Simms, whose charming and outgoing personality hid a capacity for shocking violence.

Investigations revealed traces of blood in his car, as well as part of an earring belonging to Helen. More forensic evidence, including blood stains and fibres from Helen’s clothing, were found in his flat above the pub. As clues mounted, it became clear that Simms – who allegedly had a long-standing grudge against Helen – had snatched her and killed her with awful audacity that February evening.

He was handed a life sentence, yet the absence of a body has caused unending pain for her family, who have never had the chance to properly grieve and come to terms with their loss. As Helen’s mother, Marie McCourt, has written: 'For most parents, the thought of burying their child is their worst nightmare. But I’ve spent three decades fighting to do just that.'

Marie has spearheaded the campaign for 'Helen’s Law', which if passed would mean that killers will never be granted parole unless they reveal the whereabouts of their victims’ body. The campaign has gained widespread support from the public, as well as from MP Conor McGinn, and it was given a first reading in Parliament back in 2016. Since then, movement has stalled, with an expected second reading being sidelined in 2017 thanks to the general election.

Parliamentary bureaucracy means it's unclear whether Helen’s Law will ever come to pass. A glimmer of hope came in 2018, with Justice minister Rory Stewart saying in the House of Commons that 'There is something peculiarly disgusting about the sadism involved in an individual murdering somebody and then refusing to reveal the location of the victim’s body.'

His refusal to reveal where she is down to his stubborn refusal to admit his guilt.

However, the necessity of Helen’s Law has also been called into question, with some pointing out that a refusal to disclose the location of the body is already considered an aggravating factor when passing sentence or considering granting release on parole. There’s also the troubling question of those wrongfully convicted of murder, and how Helen’s Law might prevent genuinely innocent people from ever walking free.

This has been the excuse of Ian Simms, Helen’s killer. His refusal to reveal where she is down to his stubborn refusal to admit his guilt, despite the vast amount of forensic evidence against him. As MP Conor McGinn put it, 'his guilt has only been confirmed at every single appeals stage because of enhanced evidence against him.'

What are the other possible reasons an offender may refuse to pinpoint the location of their victims? Simple psychological sadism could be a factor. Take the most infamous example of a missing victim: young Keith Bennett, who was snatched by the Moors murderers Ian Brady and Myra Hindley while on the way to visit his grandmother in 1964.

Brady toyed with the authorities – and Keith’s anguished mother – for decades over where the child had been buried. He even sent a letter to Keith’s brother way back in 1991, teasing that he would leave 'special instructions for you alone' regarding his brother’s whereabouts. Nothing came to pass. While Brady never had any hope of parole, meaning Helen’s Law would have been irrelevant to him, the case is an example of the cruel mindset of some killers who may use the mystery of their victims’ whereabouts as a form of leverage over the authorities. Helen’s Law could rob them of this power and force them to cooperate.

It could certainly make all the difference in the case of Stuart Campbell, the man convicted of murdering his teenage niece Danielle Jones in 2001. Campbell, who had an obsession with girls of her age, was convicted purely on forensic evidence, as Danielle’s body was never recovered. Indeed, the enigma of her location made initial detective work incredibly difficult, with police having faced the dilemma of whether to swoop down on their prime suspect immediately or monitor him in the hope of being led to the captive girl.

Despite his refusal to let the family have closure, Campbell become eligible for parole in 2023.

And, while it’s true that his release was rejected, the very fact he – and murderers like him – are still technically able to petition for their freedom without revealing the whereabouts of their victim's body is reason enough for many to support Helen’s Law.