The psychology of stalking and how offenders are rehabilitated

Forensic psychiatrist Dr. Sohom Das writes an exclusive article for Crime+Investigation, looking at the psychology of stalking as well as the preventative measures that can be taken and the rehabilitation process for offenders.

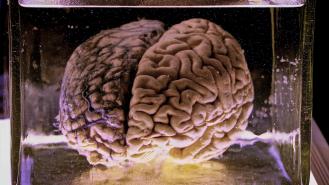

I’m a consultant forensic psychiatrist and I live and work in London. I assess and rehabilitate mentally disordered offenders, or what the tabloids might call the ‘criminally insane’. I regularly assess defendants in courts, in prisons, and in special secure psychiatric units that are reserved for the most dangerous and violent patients.

I assess stalkers in my line of work, particularly if their behaviours have been driven by mental illness. As I imagine you are, I am also occasionally engrossed in reading about high-profile cases in the media. My shrink tendencies naturally make me curious about their mentality.

What is the psychological makeup of a typical stalker?

Trick question! There is no such thing as a ‘typical’ stalker. There are lots of different motivations and intentions and a smorgasbord of disparate key personality traits. Some culprits have specific mental illnesses, yet some can be relatively high functioning and even successful. Judges, star footballers, and even politicians have been accused of this type of behaviour.

Demographically, contrary to popular belief, stalking is less likely to be committed by a stranger than an ex-partner. In fact, 80% of victims reported that they knew their stalkers in some form. Although perpetrators come in many ages, shapes, and sizes, the most common demographic is men in their 30s and the victims are women in their late teens and 20s.

From my clinical experience, the most common motivations include a desire to reclaim a prior relationship or a sadistic urge to torment the victim. This is often committed by culprits who may have been spurned or rejected. Surprise, surprise - they tend to be narcissistic, entitled, and have very sensitive, easily bruised egos.

‘How dare she leave me? Does she not know how lucky she was to have me? I will show her by constantly following her around!’

These perpetrators often have deep-rooted misogynistic views, such as ‘women cannot be trusted’. If the stalker and stalk-ee were in a previous relationship, this is often marred by controlling ‘para-stalking’ behaviour earlier; such as checking their text messages, being permanently paranoid of infidelity, and constantly wanting to know who they are with and where they are. The offender has a complete lack of insight into their weird interpersonal boundaries and feels totally justified about easily going into a jealous rage. Some even think of their actions as romantic or passionate.

Substance abuse is highly correlated and it is thought that around half of stalkers have an issue. This is not surprising considering that intoxication often leads to impulsive and disinhibited behaviour, with the user being less contemplative about the consequences of their actions. In addition to this, around half have had a personality disorder.

Personality describes the characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaviour that makes up who we are and how we feel about ourselves. An individual with a personality disorder may experience ongoing difficulties in how they perceive themselves and others, which negatively affects their well-being, mental health, and relationships. Over a quarter of stalkers don’t have either of those things. If you’re doubting my maths, some could have substance misuse issues and personality disorders simultaneously; what we call ‘comorbid disorders’ in psychiatric jargon.

In terms of individual personality traits, they often have anger and insecurity stemming from childhood. Perhaps they had unsupportive or lax parental care or attention. Perhaps they were overlooked for more charming, intelligent, or cute siblings. Perhaps they were bullied at school.

Although there are exceptions, stalkers often tend to be isolated and marginalised with a limited support structure. They are therefore usually socially inept and inexperienced. Often their targets are their primary focus simply because they have little else going on in their lives. If they tend to have little romantic success, then they might cling obsessively to a previous romantic bond or a misinterpreted hint at a potential future partner.

One rare but fascinating sub-group (at least, to me) would be when the perpetrator has a psychotic over-identification with the victim. This might involve a delusional disorder, such as erotomania; the stalker believes that another person, often somebody prestigious or famous, is in love with them. They are disconnected from reality and are exactly the kind of people I would assess; either to prepare expert evidence to assess whether their psychiatric illnesses affected their behaviour (and therefore, their criminal culpability) or within the confines of secure psychiatric units (for long-term rehabilitation until I deem they are safe enough to be released into society).

These delusional stalkers often don’t realise that what they are doing is wrong. They might be convinced that they are in relationships with famous celebrities. No amount of evidence to the contrary can shake their beliefs – amazingly, even if their very victim tells them to their face to leave them alone. One man who I assessed with schizophrenia was told this by the famous target of his affections, but assumed that the denials of love were just a test.

These culprits are potentially easier to spot and catch; due to their erratic behaviour and because they do not try to hide their actions, which they see as grand romantic gestures. Although potentially dangerous, these people are theoretically relatively straightforward to treat; I can potentially section them and anti-psychotic medication can potentially ‘cure’ this type of thinking (or at least curtail it).

Of course, it’s not that easy. There are a whole host of complications, such as side effects from medication and convincing them to remain compliant with treatment after they have been discharged from the psychiatric unit.

The good news is that if they do manage to gain insight after their psychosis has been treated, and if they continue taking their meds, their risk of reoffending is actually very low. For other people, no amount of medication can reverse their behaviour, and legal interventions are necessary (from restraining orders to actual jail time).

If you are interested in the psychological processes behind a range of crimes and offences (through the lens of a forensic psychiatrist), check out my YouTube channel, A Psych for Sore Minds.

This video is a deep dive on stalking, including a real-life case.