Ted Kaczynski: 6 facts about the Unabomber

American terrorist Ted Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber, is a name that invokes not just dread but fascination. What makes him so interesting? Unlike many killers, who act out of impulsive rage or personal vendettas, Kaczynski’s actions were rooted in a radical ideology.

Motivated by his extreme beliefs, Kaczynski launched a 17-year campaign of terror that killed three Americans and injured many more. For almost two decades the FBI was desperate to catch the lone wolf bomber, who made a habit of targeting universities and airlines.

What’s interesting, though, is that Kaczynski’s story isn’t just about his crimes. There are extraordinary contradictions at play. His combination of academic brilliance, self-inflicted isolation and methodical violence sets him apart as a truly unique criminal.

1. A lonely child prodigy

Ted Kaczynski wasn’t your average kid. An IQ of 167 saw him skip several grades and fast-track his way to Harvard University at just 16 years old. But his academic brilliance came at a cost. Ted struggled to connect with his older and more socially mature peers.

Kaczynski also took part in an infamous psychological study run by Dr. Henry Murray during his time at Harvard. The study became infamous in hindsight. Participants were asked to write essays about their beliefs and then subjected to harsh, almost cruel interrogations. Ted endured over 200 hours of this. Today, some psychologists interested in the backgrounds, motives and psyches of criminals, believe it planted the seeds of his later distrust for authority.

It’s interesting to think about how this bright young mind may have been shaped—or twisted—by these experiences.

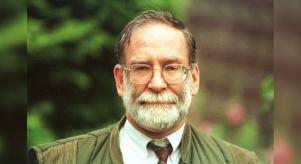

2. The youngest professor at Berkeley

At 25, Kaczynski had earned a Ph.D. in mathematics from the University of Michigan and become the youngest assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley. But just two years into his seemingly dreamy academic career he resigned with little explanation.

3. The hermit of Montana

Kaczynski vanished from mainstream society in the early 1970s. His destination? A remote cabin in the Montana woods. He built the cabin with his bare hands and lived off the land with no electricity or running water. Kaczynski spent his days writing and reflecting on what he saw as the growing dangers of industrial society.

It sounds almost poetic. A man rejecting modern society to embrace nature. But his cabin ultimately became the breeding ground for his radical ideas.

Kaczynski’s first target was a professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. In 1978 he disguised a homemade explosive device as a parcel and addressed it to the professor. But it never reached the recipient. A security officer opened the package, which exploded and caused minor injuries to his hand. The bombing was crude compared to Kaczynski’s later devices, which resembled the sophisticated bombs used in attacks like the Bologna massacre of 1980.

4. The manifesto that changed everything

In 1995, Kaczynski mailed a 35,000-word manifesto, Industrial Society and its Future, to several major newspapers. He demanded it be published or he’d continue his bombing spree. Surprisingly, The Washington Post and The New York Times agreed, reasoning that it might save lives.

What’s fascinating is how this act—intended as a threat—led to his capture. Ted’s brother, David Kaczynski, read the published manifesto and recognised the writing style. It was David’s tip to the FBI that ended Ted’s reign of terror.

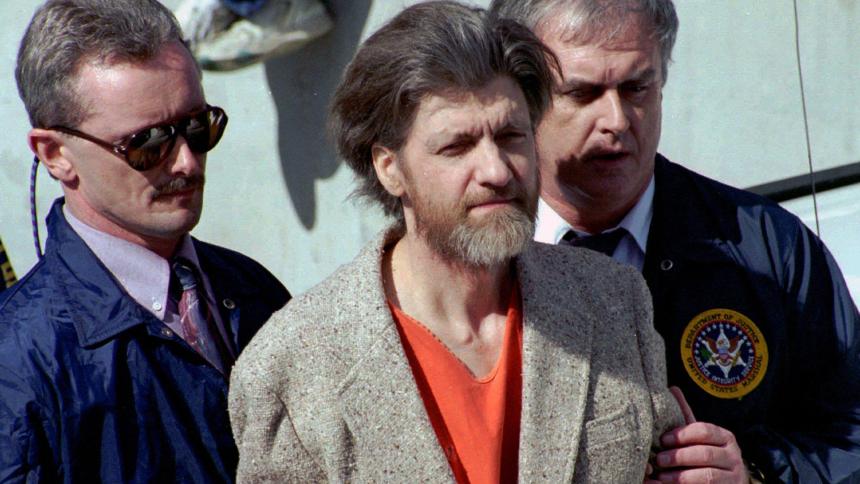

5. Life behind bars

Kaczynski was arrested in 1996 and charged with multiple crimes. This included mailing bombs that killed three people and injured 23 others. He pleaded guilty to avoid the death penalty, a fate reserved for criminals like Oklahoma City Bomber, Timothy McVeigh. Instead, Kaczynski was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

He died aged 81 at the ADX Florence supermax prison in Colorado.

6. A paradoxical legacy

Ted Kaczynski’s crimes are universally condemned. But there’s another angle to his story. There’s no denying his ideas have sparked uncomfortable discussions about technology and its impact on society and the environment. It’s a perspective that many can relate to, especially in today’s current climate.

It’s a strange legacy and poses an interesting question: How do we reconcile the thoughts of a man whose ideas, stripped of their violence, might resonate with environmentalists, technophobes and even ordinary citizens today?