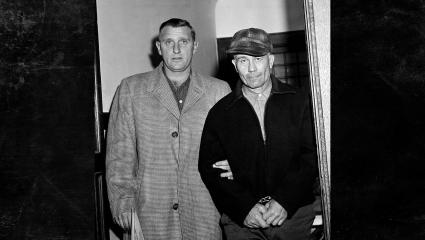

Donald Henry 'Pee Wee' Gaskins: The unassuming serial killer

Donald Henry Gaskins didn’t fit the image of a monster. Small in stature and softly-spoken, he was nicknamed ‘Pee Wee’ as a boy and that title followed him into adulthood. But behind his unassuming appearance was one of South Carolina’s most brutal killers. His crimes spanned decades and left an indelible scar on the region.

A childhood of chaos and cruelty

Gaskins was born in Florence County, South Carolina, in 1933. Sadly, his early life was marked by neglect and violence. Not only was he raised in poverty by a single mother, but he also endured constant bullying for his size. His anger turned outward when he entered his teenage years. Gaskins fell in with a gang, committing burglaries and assaults, and earned a reputation for volatility.

At 13, Gaskins was sent to reform school for an attempted rape. During his time there he experienced severe abuse, which he claimed shaped his need for control and power over others. What might have been a chance for rehabilitation turned into an incubator for his darkest impulses.

A murderer in plain sight

Gaskins kicked off his killing spree in the late 1960s. His victims? Hitchhikers and drifters travelling along South Carolina’s highways. Gaskins would lure them into his car with friendly small talk, only to reveal the depths of his violence once they were alone. He later referred to this period as his 'coastal kills', a clinical phrase for a spree of unimaginable cruelty.

Teenagers, young women and even the elderly were targets. He often described his murders with chilling detachment, claiming they fulfilled a compulsion he could not resist. 'It made me feel like somebody,' he once said.

Evading justice

For years, Gaskins evaded capture. Part of his success lay in his ability to blend in. Neighbours saw him as a quiet odd-job man, someone who attended local events and kept to himself. His small stature and affable demeanour worked in his favour, disarming suspicion. It’s a façade that’s also helped notorious killers like the ‘Angel of Death’ get away with murder for so long.

Another factor was the era. In the 1960s and 70s, US law enforcement lacked the centralised databases and forensic tools that might have linked his crimes.

Gaskins’s dual life as both a random killer and a paid hitman further muddied the waters. While some murders were opportunistic, others were calculated, committed at the request of local criminals. These mixed motives made it hard for investigators to establish a clear pattern.

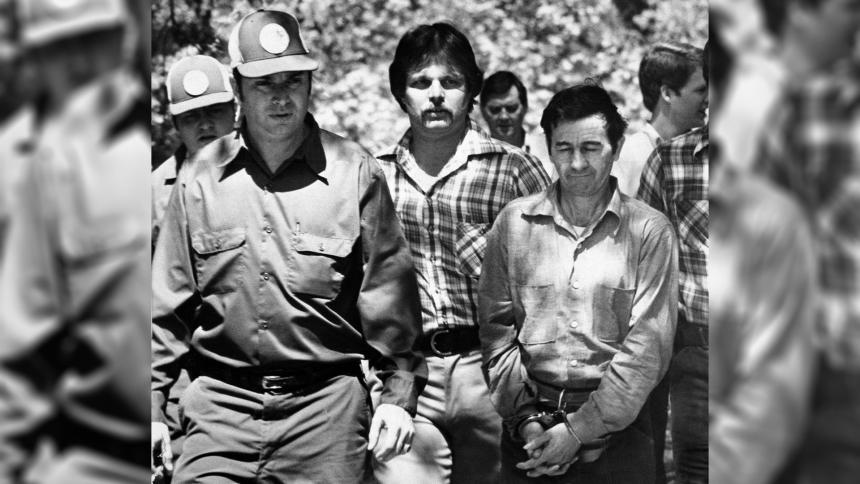

The beginning of the end

Gaskins grew careless in 1975, and it marked the beginning of his downfall. Police became suspicious after the disappearance of a 13-year-old girl and several others close to him. A search of his property revealed shallow graves containing human remains. Gaskins confessed to a staggering number of murders when confronted with the evidence, claiming to have killed over 80 victims.

His confessions were delivered with a chilling lack of remorse. Gaskins described his crimes with a cold detachment, as if recounting mundane events.

Violence even behind bars

Even imprisonment couldn’t curb Gaskins’s violent tendencies. In 1982, he orchestrated the murder of a fellow inmate, Rudolph Tyner, using a homemade bomb. Gaskins claimed he had been hired to carry out the crime, describing the act with the same calculated indifference that marked his earlier murders. His punishment? The death penalty.

Gaskins was executed on 6th September 1991 in the electric chair. Only hours earlier, he had tried to kill himself by cutting his wrists.

Why don’t we talk about him?

His crimes were horrific, but Donald Henry Gaskins’s name isn’t as well-known as other serial killers. Why? His victims were often individuals on the margins of society, whose disappearances garnered little public attention. Unlike high-profile killers with distinct media narratives, Gaskins’s crimes were scattered and untheatrical, making them harder to sensationalise.

Timing also played a role. Gaskins operated during a period of prolific serial killers, including Ted Bundy and John Wayne Gacy, whose crimes overshadowed his in the national consciousness.

Lessons from the forgotten

The crimes of Donald Henry ‘Pee Wee’ Gaskins continue to challenge our assumptions about safety and evil. The highways and small towns he haunted remain reminders of a time when one man’s darkness overshadowed the light of an entire community. And for the rest of us, his tale is a cautionary one: not all monsters stand out — they often blend into the crowd, unnoticed until it’s too late.